- A Short History of Wedding Invitations

- The Etiquette of Online Wedding Invitations

Wedding invitations have been around for a really, really long time. Like, a really really long time. In some ways they’ve changed a lot, and in others, not so much.

Here’s a brief history.

Long ago before invitations were printed — in fact, so long ago, I couldn’t find a solid date, but think definitely before moveable type was invented in 1447 and also some vague time before the Middles Ages, which began in the 5th century — town criers, if a family hired one, walked through the streets and announced weddings. If you heard the announcement, you were invited to the wedding. In the Middle Ages, nobility sent invitations with the help of monks, known for their calligraphy. But seeing as most people couldn’t read, wedding invitations weren’t exactly the norm.

Literacy improved in the mid-fifteenth century, and the upper class, super-excited to read, embraced invitations. Ink back then was messy stuff, so a piece of tissue paper placed over the invitation kept print from smudging — a practice we retain today even though it’s completely unnecessary. Mass-produced fine wedding stationery as we know it emerged around World War II, when printing advances made invitations more affordable. So the middle class jumped on board and sent wedding invitations in the style of the upper class. In fact, this encouraged an influx of etiquette books — to assist the middle class with upper class invitation protocol they had no way of knowing.

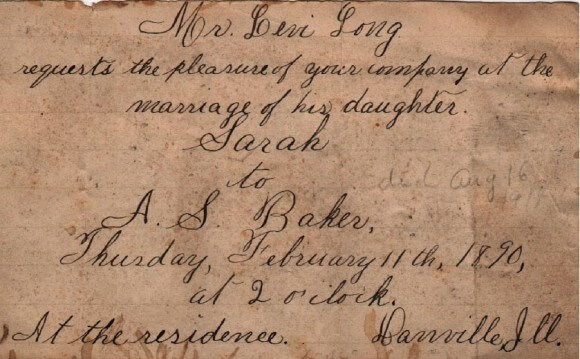

And about the invitation pictured here …

The wedding invitation of Apollos Baker and Sara Long (beware annoying pop-ups if you click through) is from 1890 and handwritten, which wasn’t uncommon for small weddings in particular. The invitation says “at the residence,” which is simply a formal way of saying it’s at the issuer’s home. Note that no address is included. Wedding invitations historically don’t include addresses on invitations. There has always been a preference towards a cleaner presentation with few extra words. I assume too that since jumping on a plane wasn’t an option, out-of-towners were less likely a factor. So you invited close friends and family who were locals, and they for sure knew your address.

At first glance, I thought I saw an error in the invite — a bit of etiquette protocol that’s less known today, but I figured the Victorians would be on top of. But turns out I’m mistaken. Typically, you request the “pleasure of your company” at social events, such as wedding receptions when not all are invited to the marriage ceremony. The “honour of your presence” is used for religious events, like marriage ceremonies. However, Crane & Co., a 200-year old stationery company, points out that marriage ceremonies that don’t take place “on sanctified ground” (i.e. your home) should, in fact, use “the pleasure of your company.”

I’m trying something out: I’m going to give the short history of some bit of etiquette protocol in one blog post, then detail its modern etiquette in another post. So please return for the second part of this post early next week!

It's good etiquette to share what you like!